SHOT Show 2026 Engineering Observations | FORESEEN OPTICS

A system-level reflection for handgun manufacturers, optical engineers, and product managers

From our observations at SHOT Show 2026, one conclusion has become increasingly clear:

a red dot should be a native part of the handgun, not an external add-on.

This is not a marketing slogan, but a clear engineering judgment.

Over the past decade, the adoption of handgun red dots followed a path of “mount it first, then try to make it stable.”

Today, native interface designs—represented by COA (A-CUT)—are proving a deeper, more fundamental logic:

When an optic is treated as part of the structure rather than an attachment, reliability, user experience, and overall system performance all make a step change forward.

I. Looking Back at the Development Path: Three Generations of Engineering Paradigms

1. Accessory Era (Add-on / Accessory Era)

The defining feature of this stage was simple: the red dot was treated as an aftermarket accessory.

- The red dot was mounted on top of the slide using two vertical screws

- Recoil resistance relied mainly on screw tension

- Horizontal shear forces were passively handled by friction between the screws and the mounting surfaces

- The optic’s overall structure did not consider lowering the mounting base, resulting in poor shooting visibility and often blocking the iron sights

The problem is this:

A pistol slide is a structure that moves back and forth at high frequency and very high acceleration. Under such conditions, any solution that relies on friction and tension to carry shear will inevitably face problems such as loosening, fatigue, and loss of zero. After mounting a red dot, shooters are always worried that the optic might fail at a critical moment, causing aiming failure.

2. Adaptation Era (Plate / Footprint Era)

To address compatibility, the industry moved into the Plate era.

Typical characteristics:

- A three-layer structure: slide → adapter plate → red dot, with later designs evolving into a two-layer slide → red dot direct-mount approach

- Support for multiple footprints (RMR, Docter, RMSc, etc.)

- Rapid ecosystem expansion and a lower barrier to entry

Engineering trade-offs:

- Introduction of classic tolerance stacking issues

- Each interface becomes a potential point for loosening, shift, and stress concentration

- A longer structural chain, making system reliability analysis more complex

- All shear forces are concentrated on two mounting screws; repeated long-term impact inevitably leads to point-of-aim shift

A view on the next 5–10 years

From an industry reality standpoint, plate-based solutions will remain one of the mainstream options over the next 5–10 years, for several reasons:

- Relatively lower machining difficulty, making it easier for small and mid-size handgun manufacturers to adapt existing production lines

- A mature footprint ecosystem already established in the market

- More controllable entry costs for new brands and new platforms

However, it’s important to note that:

As direct-mount designs improve and manufacturing gets more precise, the plate solution is lasting longer than many expected—while naturally paving the way toward native integration.

In other words, the plate is not disappearing overnight; it is being structurally absorbed.

3. Native Integration Era (Native / Integrated Era)

Native integration does not mean “getting rid of screws.” It means a fundamental shift in how loads are carried.

Core takeaway:

From “hanging” to “embedded.”

In traditional red-dot mounting, the idea is essentially this:

use two vertical screws (M3.5 or similar) to fight the massive shear forces generated by the slide’s back-and-forth motion.

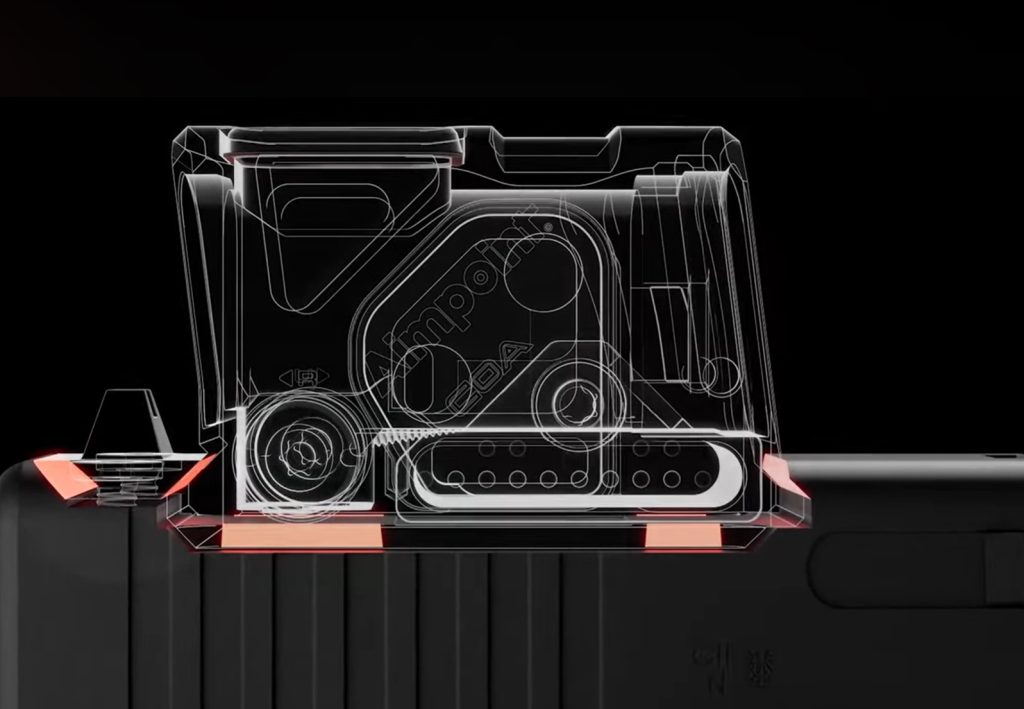

The core idea behind A-CUT style interfaces is different:

the red dot becomes part of the slide’s structure, instead of being suspended above it.

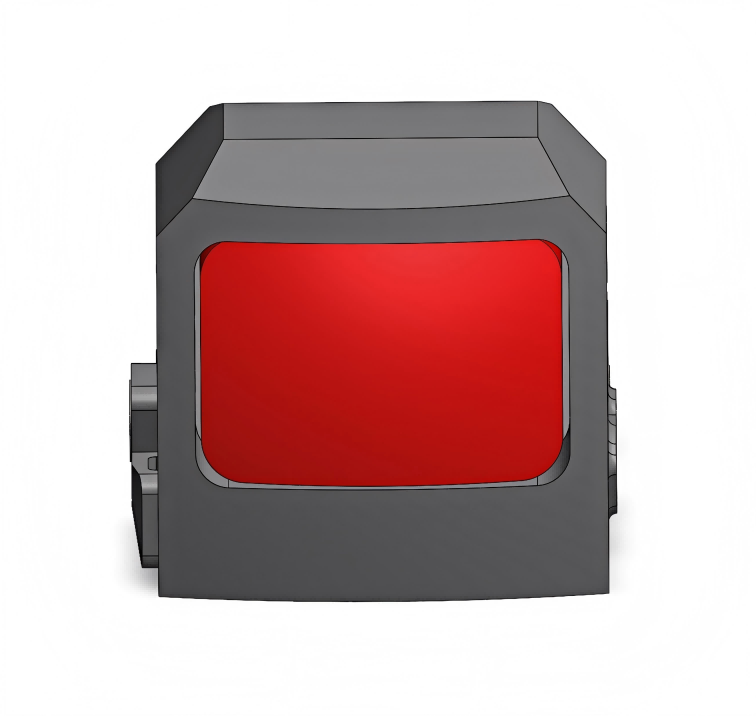

II. Breaking Down the Structural Advantages of Native Interfaces

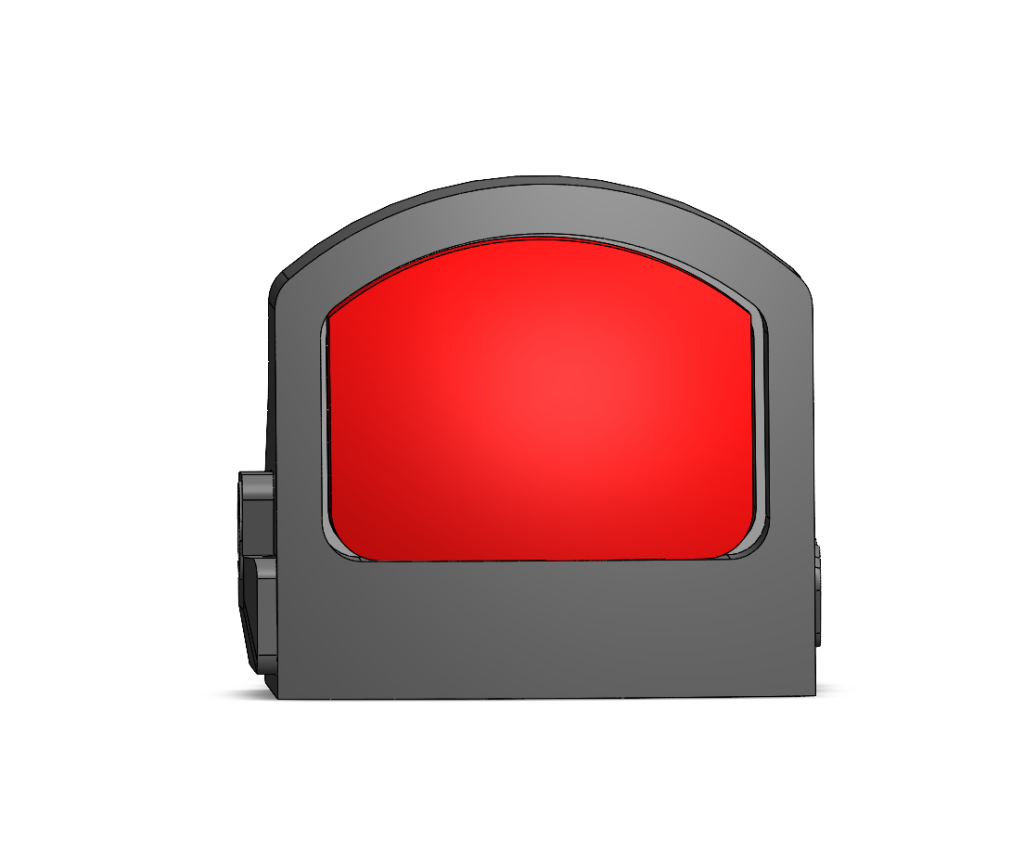

1. Mechanical Interlock (“Ski-Boot Effect”)

This structure is often described in simple terms as:

like a ski boot clicking into a binding on skis.

The key point is mechanical interlock, not friction.

Forward Toe Lock

- The front of the optic is designed with a raised lip

- This lip fits directly into a matching hook or slot at the front of the slide

Engineering logic:

- At the moment of firing, inertia pushes the optic forward

- That force is absorbed directly by the solid metal walls of the slide

- The screws are no longer responsible for carrying shear loads

2. Redistributing Recoil Loads

The problem with traditional designs

- Screws are asked to do two jobs at the same time:

- provide vertical clamping force

- resist horizontal shear forces

- Under high-frequency firing, this easily leads to metal fatigue

Rear Wedge Lock

- The rear uses a slanted wedge structure (which can also serve as the rear iron sight)

- When the screws are tightened:

- the wedge pushes the optic forward as a whole

- forcing it into constant, active engagement with the front hook

The result:

- A true structural lock is formed

- Screws are reduced to a supporting role, mainly providing clamping force

- The recoil-resistance path shifts from “screws → friction” to “metal → metal”

3. Ultra-Low Center of Gravity and Deep Integration

The A-CUT patented cut allows the optic to:

- mount deeper in the slide

- place its center of gravity closer to the slide’s axis

Torque optimization effects:

- The flipping torque generated during slide reciprocation is significantly reduced

- Long-term stress on the mounting base and locking structures is minimized

- Optical elements and electronic components gain indirect protection

III. Control Shifts Back: Who Gets to Define the “Interface”

Handgun manufacturers: Interface Owners

- They understand slide stress distribution and the locking cycle better than anyone.

- That puts them in charge of deciding:

- where the cut is placed

- how deep the cut goes

- whether it affects structural strength or ejection reliability

- They also control the conditions needed to achieve the lowest possible sight height.

Optics manufacturers: Performance Owners

Once the interface is standardized, the real competition for optics makers shifts to performance, including:

- interference-aware design (larger windows, smarter internal layout)

- stress decoupling, such as:

- shock isolation at the base

- “floating” optical assemblies

- long-term zero retention and reliability validation

IV. The Endgame of User Experience: Zero-Height Feel

True adoption should not depend on training users to adapt to the gear.

The ideal outcome is simple:

- raise the pistol, and the dot is already there

- the red dot naturally appears along the same visual path as the iron sights

- no need to change existing habits or muscle memory

Only when the red dot truly sinks into the slide does the user experience shift—from something that must be learned to something that feels instinctive.

V. FORESEEN OPTICS’ Position and Path to Collaboration

At FORESEEN OPTICS, we’ve always held one basic belief:

the platform and the use case define where optical systems should go.

That’s why, when we work with handgun manufacturers, our focus is on:

- jointly defining a true native interface standard

- building optical engines that are designed specifically around that interface

The system-level value is clear:

- lower sight height over bore

- higher overall firearm reliability

- lower long-term maintenance costs

- stronger platform-level differentiation

Final words

The plate solution is not a mistake—it was a necessary stage in the evolution.

But from an engineering perspective:

the endgame for handgun red dots is the “disappearance” of the base, and the fusion of structure and optic.

This path is harder and slower, but it leads to higher-level OEM/ODM capability and truly sustainable, system-level competitiveness.

If you’re developing a next-generation handgun platform, or thinking about how to build long-term advantages in global markets, we welcome further conversation with FORESEEN OPTICS.