An article about How FOV, Eye Relief, Exit Pupil, and Prism Diameter Together Determine “Usable Field of View” and How Comfortable It Is to Wear.

Why do some binoculars feel more open and comfortable to look through at the same magnification, while others give you dark edges and don’t fill your view? The answer isn’t a single spec—it’s the combined result of a set of optical and mechanical constraints.

Quick Take: Key Factors for Choosing Binoculars

At the same magnification, the difference in experience usually comes down to whether your eyes can fully and stably use the claimed field of view. This depends on four coupled parameters: Field of View (FOV), Eye Relief, Exit Pupil, and Prism Clear Aperture.

- FOV shows how wide the view can be in theory, but doesn’t guarantee bright edges, sharp corners, or that you’ll see the full field comfortably.

- Eye Relief and Exit Pupil determine the “eyebox”: how much your eyes can move, whether you wear glasses, or if your eye position shifts slightly—without seeing black edges or vignetting.

- Prism Clear Aperture sets the mechanical limit of the field: if it’s too small, it can block light at the edges, reduce edge brightness, shrink the usable view, and make the claimed specs work only if your eyes are in the ideal spot.

What “Usable Field of View” Really Means: Turning Specs into Real Experience

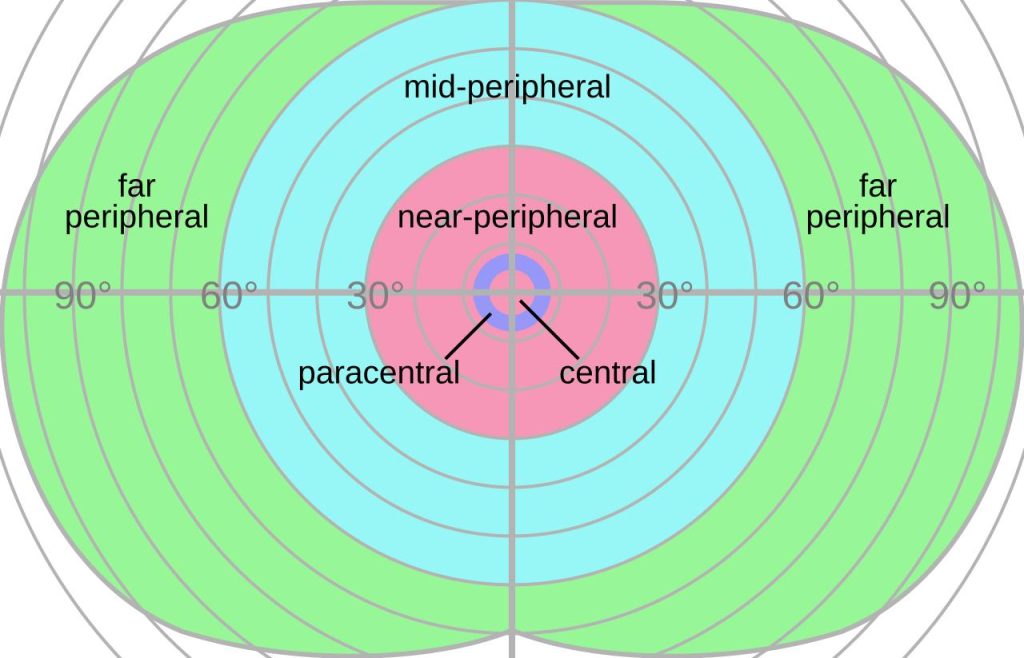

We define “usable field of view” as the full field a user can see stably and comfortably from a natural eye position (including when wearing glasses). It requires all of the following:

- The field edge is visible, without being cut off by short eye relief or sensitive eye positioning.

- The edges are not overly dark, meaning light is not significantly blocked by limited prism aperture or internal baffles, which would reduce edge brightness.

- Image clarity and distortion across the field are acceptable, so edge softness or rolling-ball effects do not noticeably interfere with observation.

As a result, two binoculars both labeled 8× with a claimed 8.0° FOV can feel very different in use: one lets you take in the full view easily and pan without blackouts, while the other shows dark edges with even slight eye misalignment and clearly darker edges.

1) FOV: Claimed FOV, Angular View, and “Edge Trade-off”

Field of View (FOV) is usually specified in two ways: in degrees (°) or as width at 1,000 m (m/1,000 m). The two can be converted:

Width W (m/1,000 m) ≈ 1000 × 2 × tan(θ/2) (θ=true field angle)

There’s also a concept closer to actual experience: Apparent FOV (AFOV). For small angles,

AFOV ≈ Magnification × True FOV (TFOV)

AFOV determines how large the image feels, while TFOV determines how wide an area you can scan.

From a professional perspective, FOV is not “the bigger, the better.” To achieve a wider field, eyepiece design often requires trade-offs between distortion, astigmatism, edge sharpness, and edge brightness. What the user actually experiences is not the claimed FOV, but rather:

- Whether the edges appear noticeably soft or blurry (aberrations and modulation transfer).

- Whether scanning causes visible dizziness effects (distortion distribution).

- Whether the edges are noticeably dark (clipping caused by prism aperture and internal baffles).

2) Eye Relief: A Key Limit for Glasses Wearers and a Source of “Black Edge” Sensitivity

Eye relief refers to how far your eye can be from the last surface of the eyepiece (or the equivalent exit pupil position) while still seeing the full field of view. For users wearing glasses, the distance from the glasses to the eyes “consumes” part of the eye relief, so a longer effective eye relief is required.

Common Pitfalls in Engineering and Quality Control: A spec may list 17 mm eye relief, but glasses-wearing users still can’t see the full field. This is usually not due to “false specs,” but because the effective eye relief is reduced by structural details, such as:

- The last surface of the eyepiece is deeply recessed, reducing usable distance.

- The shape and stiffness of the eyecup/top of the ocular prevent glasses from sitting at the intended position.

- Mechanical obstructions or internal baffles at the eyepiece edge make the “claimed FOV” only achievable under ideal eye placement.

For professional users, eye relief cannot be judged by the number alone. Eyebox tolerance matters: how far the eyes can shift in any direction while still seeing the full field without noticeable black edges. This is especially critical for wide-field eyepieces.

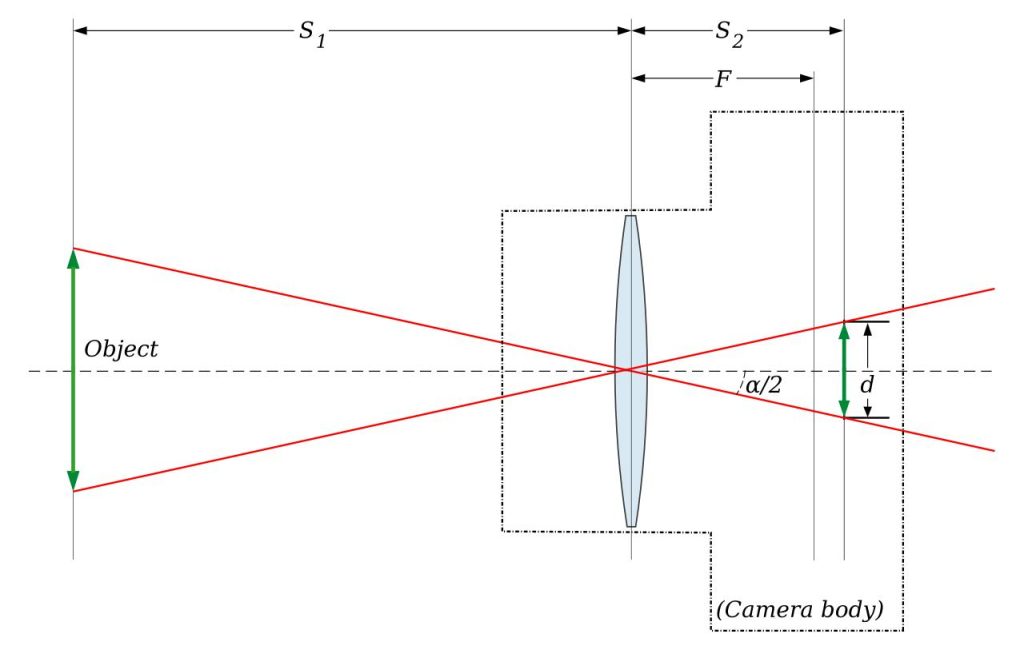

3) Exit Pupil: The Common Language of Brightness and Eye-Position Tolerance

Exit pupil diameter is one of the most easily overlooked parameters, yet it explains a lot about the user experience. Its basic relationship is simple:

Exit Pupil (mm) = Objective Diameter (mm) / Magnification

A larger exit pupil typically provides higher effective brightness in low light and allows the eye to tolerate more lateral and longitudinal movement at the same magnification, which lowers the possibility of black edges.

Bigger is not always better, though; when the exit pupil is larger than the human pupil, the extra light is just blocked by the eye, preventing further increases in actual brightness.

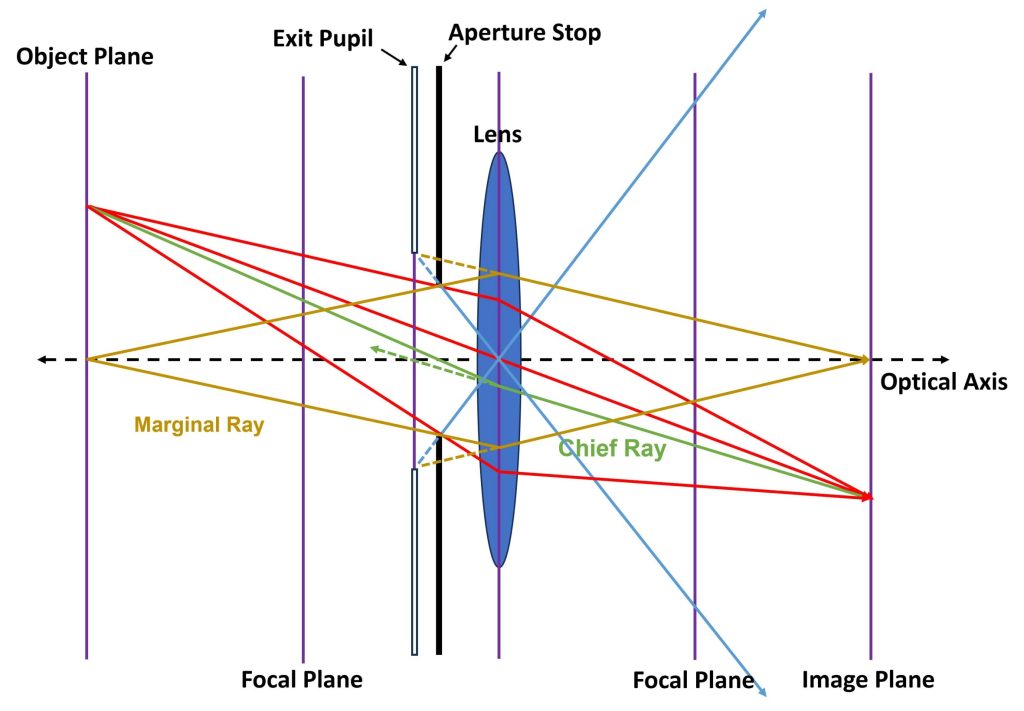

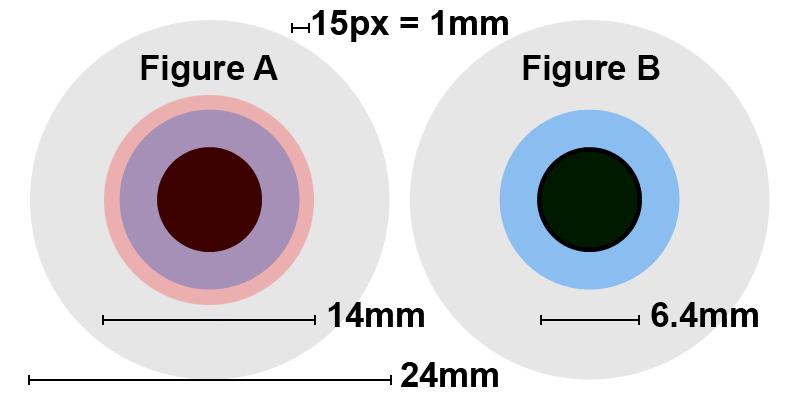

- Figure 5 | Geometric meaning of exit pupil: the position and diameter where the system delivers light to the eye. Both size and location determine viewing comfort and tolerance.

- Figure 6 | Exit pupil vs. human pupil: too small limits light entering the eye, too large mainly improves eye-position tolerance rather than increasing brightness.

Practical Recommendations (for Product Definition or Procurement Specs):

- Daytime use, lightweight and portable: an exit pupil of 3.0–4.0 mm is usually sufficient; smaller pupils are more sensitive to eye position.

- Dusk, forest, or marine use: 4.0–5.5 mm exit pupil offers more stability, especially for prolonged viewing or quick target acquisition.

- Prioritizing glasses compatibility + wide FOV: exit pupil and eye relief should be designed together; simply extending eye relief while keeping a small exit pupil or narrow eyebox can lead to a “great specs but hard to use” scenario.

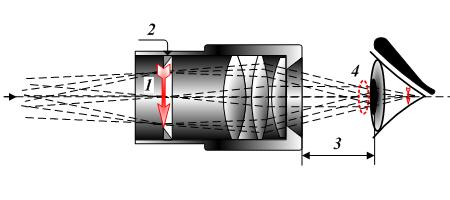

4) Prism Clear Aperture: the Hidden Variable That Sets the Usable FOV Limit

In binoculars, prisms don’t just fold the optical path—they also act as the channel that carries the field of view. For off-axis rays (from the edge of the field), the beam footprint inside the prism becomes larger. If the prism’s clear aperture is insufficient, light clipping (vignetting) occurs. The result is:

- Reduced edge brightness: the image darkens toward the edges, subjectively shrinking the field of view.

- Truncated exit pupil shape: eye position becomes more sensitive, making black edges more likely.

- Mismatch between specs and real experience: the FOV/AFOV listed on the spec sheet may hold on-axis under ideal conditions, but users struggle to use the full field in normal viewing.

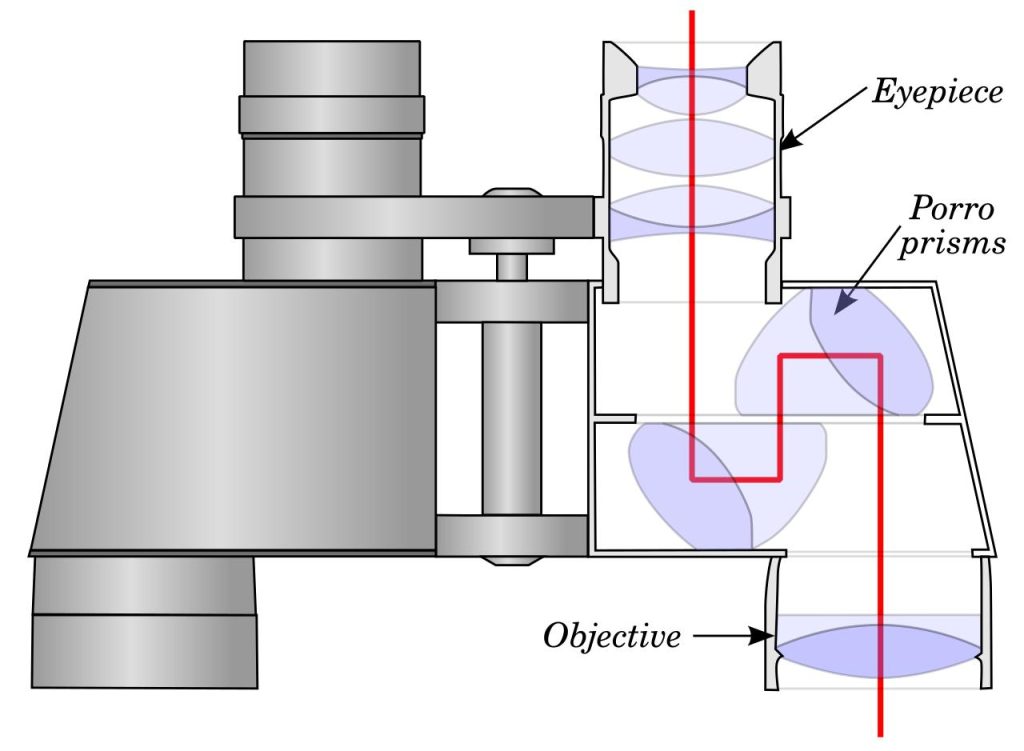

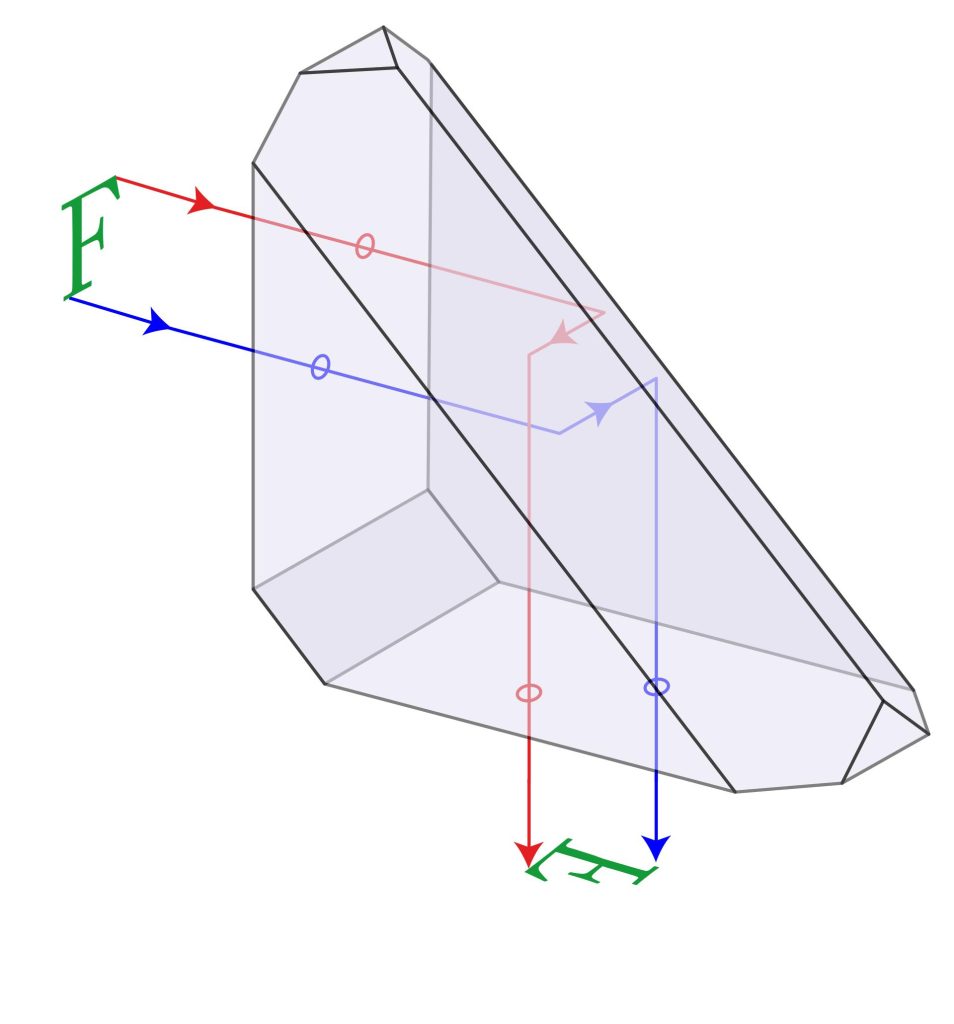

- Figure 7 | Binocular optical path and prisms: a wider field produces larger off-axis light bundles, requiring greater prism clear aperture and internal light paths.

- Figure 8 | Optical path in roof prisms: light margin at the field edges is affected by structure and clear aperture (illustration only, not a specific model).

Because of this, binoculars with the same magnification and objective size can still feel very different when in use. For example, one design appropriately matches prism clear aperture, internal baffling, and eyepiece field, while another reduces prism size or internal light paths to save money or space, but at the expense of edge darkening and increased sensitivity to blackouts.

Putting the Four Parameters into One Engineering View: From “Claimed” to “Usable”

Breaking usable field of view into three layers makes specification definition, design review, and quality acceptance much clearer:

- Optical: the eyepiece field and field stop set how large the field can be in theory.

- Mechanical: prism clear aperture, baffling, and internal light paths determine whether the edges are clipped.

- Human-factor: eye relief, exit pupil, and eyecup design determine whether users can stably see the full field.

Below is an intuitive comparison of energy and tolerance using typical configurations at the same magnification (for illustration only, not representing any specific model).

| Typical Specs | Exit Pupil (mm) | Typical True FOV (°) | Glasses Compatibility | Eye-Position Tolerance | Risk Points |

| 8×25 | 3.1 | 6.5–7.5 | Low–Medium | Low–Medium | Shorter eye relief and narrow eyebox; blackouts are more likely with wide FOV |

| 8×32 | 4.0 | 7.5–8.5 | Medium–High | Medium–High | If prism aperture is reduced, edge illumination can drop easily |

| 8×42 | 5.25 | 7.5–8.5 | High | High | Increased size and weight; higher demands on edge image quality control |

The logic behind this table is that exit pupil and eye relief determine whether you have enough freedom in eye position, while prism clear aperture determines whether there is sufficient light margin at the field edges. Overlaying these two constraints gives the upper limit of the usable field of view.

Evaluation and Acceptance: How Professional Teams Translate “Experience” into Measurable Metrics

If you are responsible for product definition, supply chain review, or incoming inspection, it is recommended to break usable field of view into actionable checkpoints:

A. Field-of-View Related: Don’t Rely on a Single Number

- Record both true FOV (° or m/1,000 m) and apparent FOV (AFOV); AFOV better reflects the subjective “image size.”

- Pay attention to edge image quality and distortion strategy: a wide-field eyepiece with poorly distributed distortion can cause “rolling ball” effects and eye fatigue during scanning.

- Assess whether the field is truly usable using edge brightness or vignetting: for the same claimed FOV, one-level darker edges versus two-level darker edges can feel very different.

B. Wearer Compatibility: Describe Using “Effective Eye Relief + Eyebox Tolerance” Instead of Just Saying “Glasses Compatible”

- Require the supplier to provide effective eye relief (considering eyepiece recess and eyecup structure) and verify that the full field edge is visible when wearing glasses.

- Test black-edge sensitivity at different eyecup heights: does slight forward/backward or vertical offset immediately cause field loss?

- For wide-field products, consider defining a “black-edge tolerance window” as an acceptance criterion (e.g., allowable lateral or longitudinal offsets).

C. Prism Clear Aperture and Vignetting: Go Beyond “Are There Dark Edges?” to “How Dark Are They?”

- Observe edge brightness across a uniform background (sky/white wall): is there noticeable ring-shaped darkening?

- Check if the exit pupil shape remains fully circular: truncation often indicates prism or internal light path bottlenecks.

- For different magnifications on the same platform (e.g., 8× vs. 10×), verify whether prism and light paths are shared: magnification changes the beam geometry, so vignetting risk may differ.

Tip: The above checks can be done without expensive equipment for initial screening. However, for mass production or dispute resolution, it is recommended to combine illuminance and imaging measurements for standardized records to avoid subjective disagreements.

Quick Selection Guide: Three “Experience Orientations” at the Same Magnification

Below is an example using a common 8× platform, showing how the four parameters can be combined into three task-oriented approaches. Use this to guide spec writing or SKU planning:

1) Wide-Field Priority (Scanning/Tracking)

- Goal: Larger TFOV/AFOV for more efficient scanning.

- Key: Prism clear aperture and internal light paths must scale together; otherwise, edge brightness and black-edge tolerance will suffer.

- Recommendation: Treat edge brightness and black-edge tolerance window as primary metrics, not footnotes.

2) Glasses-Compatible Priority (Prolonged Viewing / Eyeglass Users)

- Goal: Sufficient effective eye relief and wide eyebox for fatigue-free long-term use.

- Key: Eye relief must work in concert with exit pupil; simply extending eye relief while keeping a small exit pupil leads to “great specs but hard to use.”

- Recommendation: Prefer platforms with exit pupil ≥ 4 mm; evaluate eye relief based on effective value.

3) Size & Cost Priority (Lightweight / Entry-Level / High-Volume)

- Goal: Controllable dimensions, weight, and BOM cost.

- Key: When increasing FOV, prism aperture and edge brightness are most often sacrificed; over-compression can shrink the usable field.

- Recommendation: Define minimum experience standards in the spec sheet, e.g., limit black-edge sensitivity and edge vignetting levels.

Common Misconceptions (FAQ)

Misconception 1: Bigger FOV = better.

Wide fields require more complex eyepieces and larger clear apertures; otherwise, it just looks big but can’t be fully used.

Misconception 2: Long eye relief automatically means glasses-friendly.

What matters is effective eye relief and eyecup structure; the same 17 mm can feel very different in practice.

Misconception 3: Using BaK-4 prisms prevents vignetting.

Glass type affects refraction and exit pupil shape, but vignetting fundamentally comes from insufficient clear aperture and internal light paths.

Misconception 4: Exit pupil only affects brightness.

Exit pupil also determines eye-position tolerance, which is especially important for quick aiming or moving observation.

Conclusion: Put “usable field of view” into the specs to differentiate products at the same magnification.

Same magnification does not mean same experience. Considering FOV, eye relief, exit pupil, and prism aperture as an integrated system shows that what truly makes the user feel “wide, comfortable, and stable” is the usable field and wearer compatibility, not simply stacking up individual specs.