In binocular design, the optical path is not just an internal detail – it is the reason a product ends up wide or slim, short or long, easy or painful to assemble, and cheap or expensive to scale.

This article starts where professional programs start: target use-case and performance envelope, then works inward to prism architecture, objective/focal-length constraints, and bridge/hinge choices. Along the way, we connect each structural choice to assembly yield (collimation stability, tolerance stack, coating risk) and to the cost curve you will see in volume production.

What you will get:

- A decision framework you can use in an RFQ or early concept review

- A prism-architecture comparison focused on size, yield, and cost drivers

- Practical guidelines for compact (25 mm class), mid-size (30-32 mm), and full-size (42 mm class) platforms

- Manufacturing notes that reduce rework and improve collimation pass rate

Start with the mission profile (before you argue about prisms)

Professional programs rarely fail because of a single optical spec. They fail because the structure chosen for the optics cannot hit the mechanical, environmental, and cost targets at the same time. Before choosing a prism family, lock these items:

- Primary use environment (travel, birding, marine, tactical, astronomy, industrial inspection)

- Carry mode and volume limit (jacket pocket vs pack pocket vs chest harness)

- Low-light expectation (dawn/dusk vs daylight-only) and minimum acceptable exit pupil

- Glasses compatibility (effective eye relief requirement) and eyecup strategy

- Ingress protection and durability targets (waterproofing, fog-proofing, drop/shock)

- Target retail/transfer price and expected annual volume (this determines the cost curve you can afford)

A practical starting table (typical targets):

| Mission | Typical spec anchor | Objective class | Prism candidates | Key risks |

| Everyday carry / travel | 8x, wide FOV, fast handling | 21-25 mm | Reverse Porro, compact Roof | IPD range, eye relief, sealing in small volume |

| Birding / nature | 8x or 10x, color/contrast priority | 30-42 mm | Roof (S-P or Abbe-Koenig), Porro | stray light control, phase/mirror coatings, weight ceiling |

| Marine | 7x, stability, waterproofing | 42-50 mm | Porro, Roof | sealing, corrosion, focus robustness |

| Tactical / LE | 8x, ruggedness, repeatable collimation | 30-42 mm | Roof, Porro | shock survival, hinge stiffness, QC throughput |

| Astronomy (handheld) | 7x to 10x, brightness | 42-56 mm | Porro, Abbe-Koenig Roof | mass, tripod compatibility, pupil size vs shake |

Optics set the mass and volume ceiling (even before the housing)

Two numbers dominate packaging more than most teams expect: objective diameter and effective focal length. Objective diameter drives barrel diameter, prism clear aperture, and overall mass. Effective focal length drives the physical light-path length that the prism system must fold.

As a rule: when you push for a shorter body at the same objective and magnification, the prism system must fold a longer light path into a smaller envelope. That is where yield and cost often explode: tighter prism seats, higher sensitivity to tilt, and less margin for stray light baffling.

Three structural levers that dominate size, yield, and cost

Prism architecture: the hidden driver of width, coatings, and alignment yield

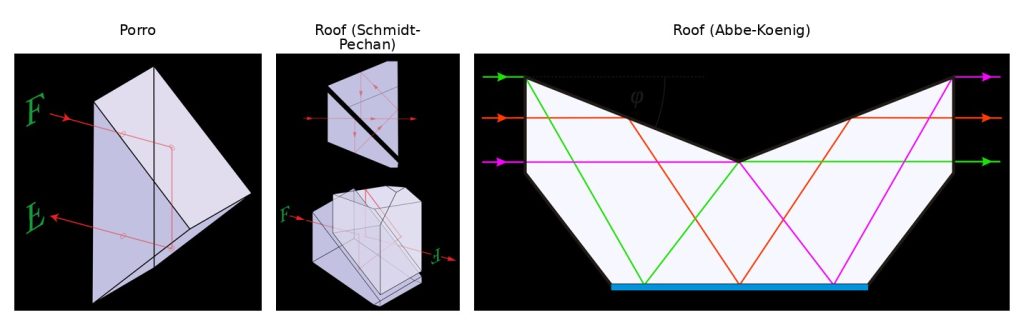

A simple field check: in Porro designs the objective and eyepiece are not coaxial, so the body looks ‘stepped’ and wider. In Roof designs the objective and eyepiece are roughly in-line, so the barrels look straight and slim. Reverse Porro compacts often look very short, with aggressive folding to reduce length.

Below is the decision logic that matters for professional customers:

- Porro (including classic double-Porro binocular layouts)

- Form factor: wider body for the same objective because the prism path creates lateral offset.

- Optical efficiency: many Porro surfaces use total internal reflection, reducing dependence on mirror coatings.

- Manufacturing: generally forgiving in angle errors compared with roof-edge sensitivity; collimation adjustment is straightforward.

- Cost curve: strong value at mid performance levels, especially when volume favors simple prism procurement and fast QC.

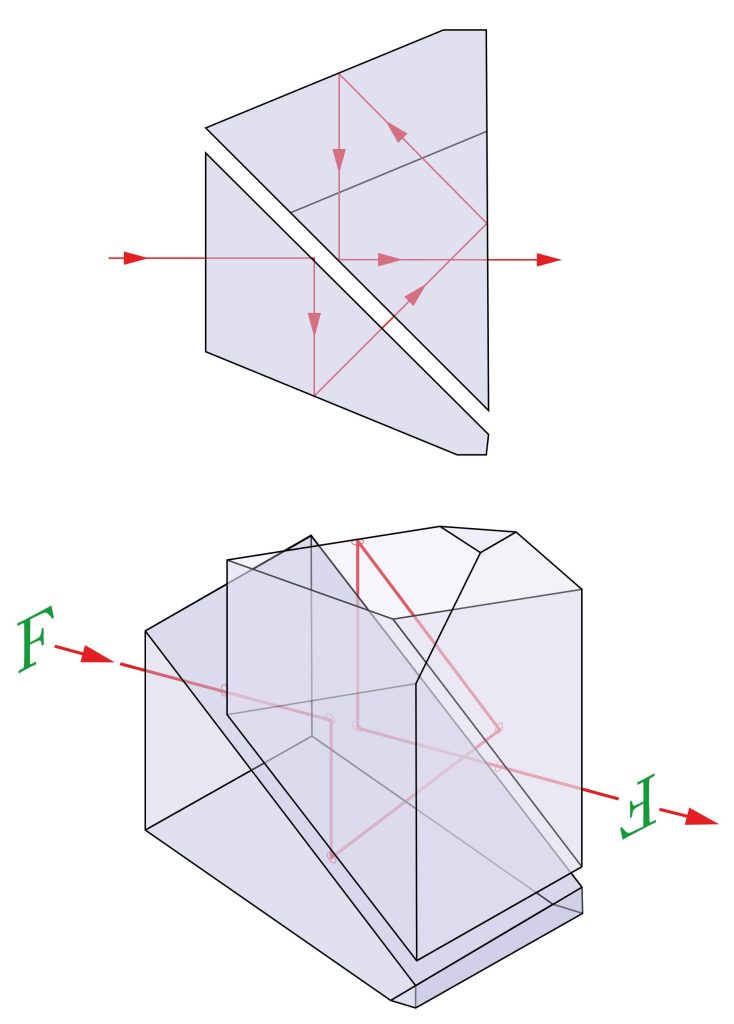

- Roof (Schmidt-Pechan)

- Form factor: the most compact width for a given objective; enables slim, in-line barrels.

- Optical efficiency: typically requires mirror coatings on non-TIR surfaces and phase correction to maintain contrast.

- Manufacturing yield drivers: roof-edge quality, prism angle control, and coating variability. Small errors often show up as contrast loss or collimation drift after shock/temperature cycling.

- Cost curve: more expensive at entry level, but scales well when coatings and prism suppliers are stable and QC is automated.

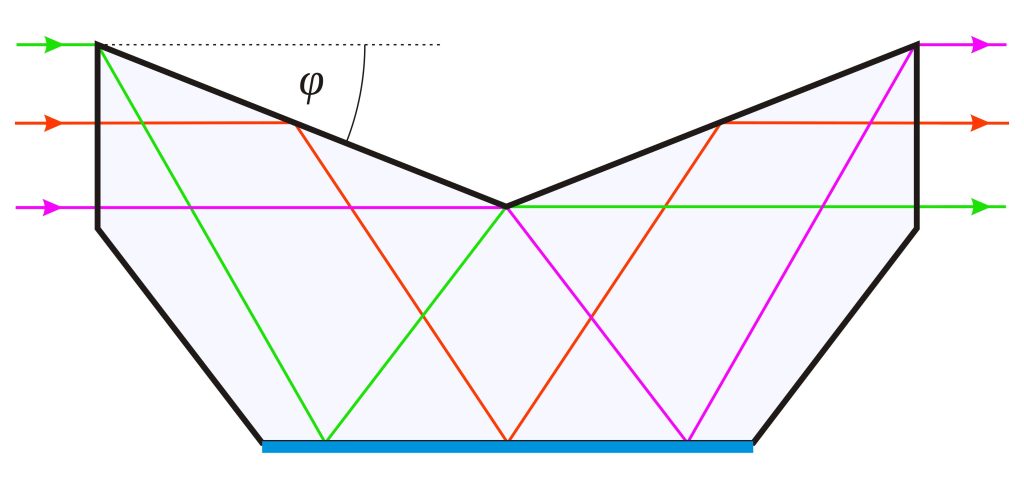

- Roof (Abbe-Koenig)

- Form factor: in-line like a roof design, but usually longer than Schmidt-Pechan for the same aperture.

- Optical efficiency: commonly uses total internal reflection, reducing mirror-coating dependence (often chosen for premium transmission).

- Manufacturing: larger prism mass and length increase material cost and housing length; alignment is still roof-family sensitive but coating stack risk is often lower than Schmidt-Pechan.

- Cost curve: favors premium, full-size lines where length is acceptable and transmission is a selling point.

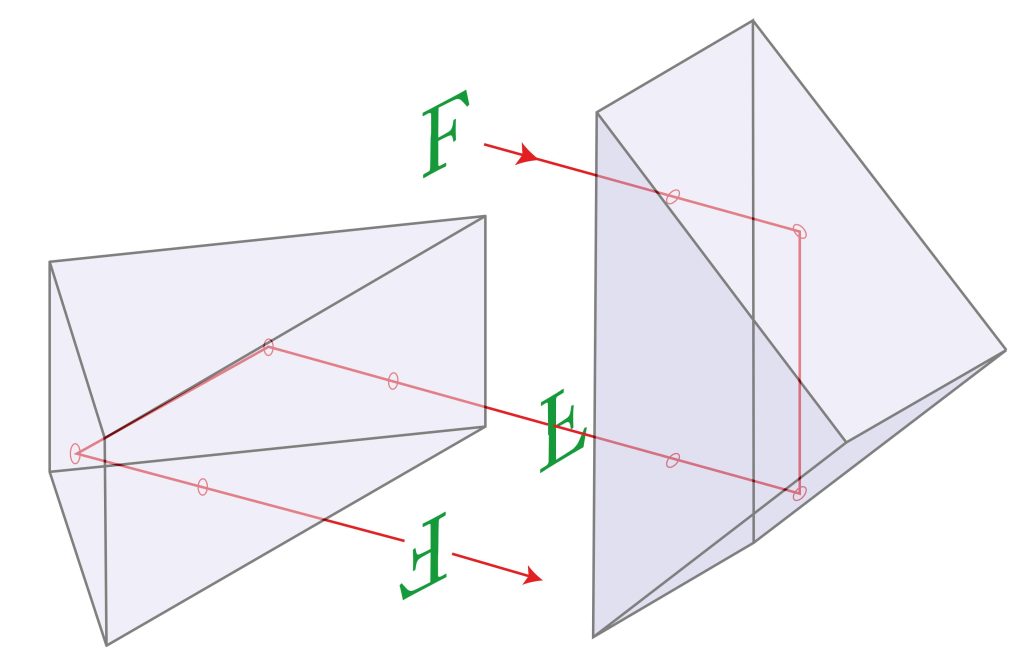

- Reverse Porro (compact-focused folding layouts)

Reverse Porro is best understood as a compact packaging philosophy: use Porro-like prisms but reverse the layout so the body can be shorter and often pocket-friendly. Its advantage is not just size – it can reach a favorable yield-to-cost ratio because it avoids some roof-edge sensitivity while still folding aggressively.

- Form factor: very short overall length; strong ‘pocketability’ when combined with a compact hinge design.

- Optical/UX: often delivers a comfortable stereoscopic feel and good brightness per dollar in the pocket class.

- Manufacturing: small parts make sealing, hinge feel, and IPD range critical; however prism tolerance can be more forgiving than many entry roof designs.

- Cost curve: attractive for 25 mm-class programs where you need compactness without paying full roof-prism coating overhead.

Objective diameter and focal length: the physical basis of length and width

Objective diameter is the simplest driver: bigger glass forces bigger barrels, bigger prism clear apertures, and higher weight. Focal length is the quieter driver: longer focal length means the optical path must travel farther before it reaches the prisms and eyepieces. If you refuse to let the product get longer, the prisms must fold more aggressively – which increases sensitivity to tilt, vignetting, and internal baffling.

Common platform classes used in product planning:

- 42 mm class: full-size, brightness prioritized, maximum volume and mass.

- 30-32 mm class: mid-size, balance of performance and portability, strong for birding/travel hybrids.

- 21-25 mm class: pocket-size, portability prioritized; 25 mm is a key engineering threshold for ‘always-carry’ products.

Bridge and hinge architecture: stiffness, IPD, and collimation stability

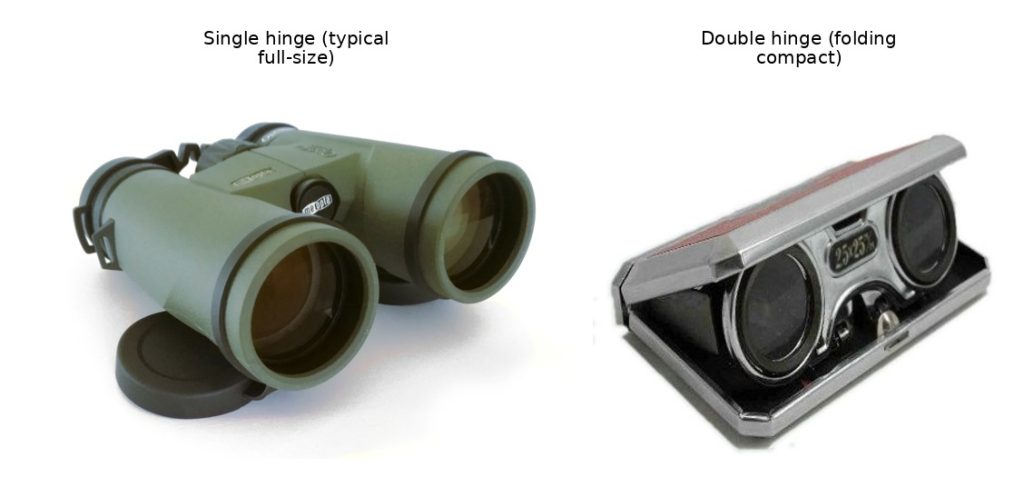

Two binoculars can share the same prism type and objective size but behave very differently in the field and in production, purely because of the bridge/hinge design. Hinges define IPD range, torsional stiffness, sealing interfaces, and how well optical axes stay aligned after shock.

Key manufacturing notes (what affects yield):

- Hinge stiffness and repeatability: if hinge torque drifts, IPD stability suffers and customers report eye strain.

- Axis-parallelism control: bridge machining and assembly must keep optical axes parallel; otherwise collimation adjustment consumes time and reduces pass rate.

- Sealing strategy: more joints and moving parts increase leak paths; this interacts directly with purge yield and long-term fog performance.

Where yield is won or lost: alignment and QC throughput

In volume production, optical performance is not the only goal – repeatability is. The same design can be cheap or expensive depending on how many minutes of adjustment it needs per unit and how stable that adjustment remains after drop/thermal cycling.

Prism selection influences this more than most BOM models capture: roof families concentrate sensitivity into roof edges and coating stacks; Porro families distribute it into larger housings and hinge stiffness.

A practical yield checklist you can use during DFM/DFMEA:

| Area | Typical failure mode | Design/Process countermeasure |

| Prism seat & clamping | Tilt or creep shifts collimation | Use hard datum surfaces, controlled torque, and adhesive strategy validated by thermal cycling |

| Coating stack (roof) | Contrast loss or batch variability | Supplier qualification, witness coupons, and incoming inspection tied to contrast metrics |

| Bridge/hinge | IPD drift, customer eye strain | Torque spec plus life-cycle test, friction materials, and consistent grease selection |

| Stray light control | Veiling glare, reduced perceived sharpness | Baffles, edge blackening, matte coatings, stop placement validated in bright off-axis tests |

| Final QC | Long adjustment time, rework loop | Standardize collimation method, automate measurement where possible, close feedback to machining tolerances |

Platform recommendations: matching architecture to your cost curve

There is no universally ‘best’ prism. The correct answer depends on the envelope you must protect: volume, mass, sealing level, performance, and the cost curve at your target volume.

Use these rules of thumb:

- Pocket-class (21-25 mm) with aggressive size targets: reverse-Porro layouts often deliver the best compactness-to-yield ratio; compact roof is the premium route when coating and sealing budgets allow.

- Mid-size (30-32 mm) performance-per-gram: roof designs dominate when slim form factor and sealing are key; Porro remains compelling where width is acceptable and value is prioritized.

- Full-size (42 mm and above) low-light programs: Porro and Abbe-Koenig platforms are strong when brightness and transmission are selling points; Schmidt-Pechan wins when you need the slimmest body.

Three common product pivots (what to change when requirements move)

Programs shift. When they do, these pivots preserve engineering sanity:

Pivot A: Make it brighter

- Increase objective class (30-32 mm to 42 mm) or reduce magnification to increase exit pupil.

- Prefer prism families with fewer coating dependencies (Porro or Abbe-Koenig) when transmission is the headline metric.

- Budget for weight: brighter almost always means heavier unless you sacrifice durability or field of view.

Pivot B: Make it smaller

- Move into the 21-25 mm class and accept the low-light trade-off.

- Use reverse-Porro or compact roof with a folding hinge to reduce length and pocket volume.

- Protect ergonomics: short bodies amplify sensitivity to eye position, eye relief, and IPD range.

Pivot C: Make it cheaper at volume

- Reduce adjustment time: design for collimation pass rate, not only theoretical performance.

- Avoid fragile cost drivers early: complex coating stacks, tight roof-edge specs, and multi-part sealing interfaces.

- Standardize platforms: reuse validated prism seats, hinges, and QC tooling across SKUs.